One of the most horrific tales of mass violence ever began just 20 years ago. During the 100 days after Easter 1994, ethnic Hutu extremists killed 1 million fellow Rwandans. The surviving 80% of the population reeled from health crises.

Health workers fled or were killed. Many who remained had been complicit in the genocide, seeding distrust in medical establishment. An estimated 250,000 women were raped. HIV became a weapon of war. Refugee camps fell to one of the century’s largest cholera outbreaks. Rwanda was left with the world’s highest child mortality and lowest life expectancy at birth. Fewer than one in four children were vaccinated against measles and polio.

“Whether survivor, perpetrator, or member of the diaspora, no Rwandan emerged unaffected,” writes Rwandan minister of health Agnes Binagwaho in The Lancet on Apr.4 , in a study co-authored with Dr. Paul Farmer and a team of international public health experts. “Much of the rest of the world stood idly by.”

Few imagined that Rwanda, a country the size of Maryland, would so soon—if ever—serve as an international model for health equity.

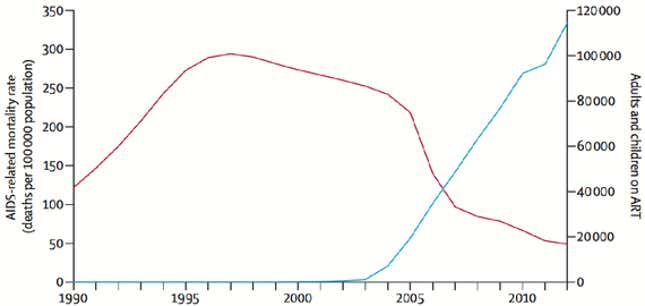

Just two decades later, that life expectancy has doubled. Vaccination rates for many diseases are now higher than those registered in the United States—more than 97% of Rwandan infants are immunized against ten different diseases. Child mortality has fallen by more than two thirds since 2000. New HIV infection rates fell by 60% between 2000 and 2012, and AIDS-related mortality fell by 82%. HIV treatment is free.

“In the last decade, death rates from AIDS and tuberculosis have dropped more steeply in Rwanda than just about anywhere, ever,” said Farmer. Perhaps the most renowned name healthcare delivery to the world’s poor and marginalized, Farmer says he can think of no more dramatic example of turnaround.

“Some assume that such awful circumstances led to a tardy but emphatic humanitarian response,” Binagwaho and colleagues write today. “Such assumptions are wrong. Many were ready to write Rwanda off as a lost cause.” In 1995, Rwandans received an average of 50 cents per person in foreign assistance for health. Only a decade ago did Rwanda receive its first major international grants to treat HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria.

“Some development experts even advised withholding primary care services from children to stave off population growth and prevent what they called a ‘Malthusian abyss,’” the Lancet authors write.

The unlikely success hinged on a national development plan that championed health equity, a constitution that formally named a universal right to health, a community-based national health insurance system, and community health workers. (In each of Rwanda’s 14,837 villages, three elected community health workers are trained and equipped to disseminate resources and basic elements of care.)

In 1998, a new government launched a consultative process to create a national development plan based on inclusive social cohesion and health equity, involving substantial investments in public health and healthcare delivery. Community-based health insurance and performance-based financing systems began in three of the country’s districts and expanded nationwide in 2004.

In 2010 the Ministry of Health instituted a three-tiered premium system based on Rwanda’s socioeconomic assessment system, ubudehe. There was simultaneous decentralization and integration of health services, increasing domestic funding alongside external resources. By 2010, 58% of foreign assistance was able to be channeled through Rwandan national systems, compared with an average of 20% in post-conflict settings.

“This strengthening of public sector capacity is both cause and effect of a focus on national ownership and oversight,” Binagwaho and colleagues write. “Such an approach to shared accountability has also leveraged increasing investment from the Rwandan government.” Rwanda was able to dedicate 22% of general government expenditure to public health in 2011, for services like gender-based violence prevention and family planning.

“Counter to some experts’ forecasts after the genocide, reduced child mortality has correlated closely with higher family planning uptake. More children surviving means parents no longer have additional children to offset the expected deaths of some.”

This post originally appeared at The Atlantic. More from our sister site:

Meet the company that secretly built the “Cuban Twitter”