Shortly after Thabo Mbeki, the former South African president, began his flirtation with Aids dissidence in 2000, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) was created to respond to the HIV crisis in the country and the government's reluctance to deal with it.

Although closely aligned with the ANC government, the TAC engaged politically and launched various court challenges to force a change of heart on the part of the government and, ultimately, in order to ensure that every HIV-positive person who could not afford it was provided with antiretroviral (ARV) medicine by the state.

The TAC ran a brilliant and strategically astute campaign to mobilise the public, trade union organisations and other civil society groups behind its cause. Its trump card in this campaign was section 27(1) of the constitution , which states that everyone has the right to have access to healthcare services, including reproductive healthcare.

Like other social and economic rights contained in the South African bill of rights – including the right of access to housing, sufficient food and water; and social security – the right to healthcare is not absolute. It requires the state only to take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of each of these rights.

At the time of the drafting of the bill, some politicians and academics opposed the inclusion of these rights, arguing that it would not be possible for judges to enforce these claims as they would be required to make policy choices best left to the democratically elected branches of government. But given the vast discrepancies in wealth – often based on race – caused by apartheid and the fact that many citizens did not have access to basic services at the dawn of democracy, the drafters of the constitution believed that it was imperative to include not only traditional civil and political rights in the constitution, but also justiciable social and economic rights. Otherwise the very legitimacy of the constitutional enterprise would be at risk.

South Africa's constitutional court at first dealt cautiously with the interpretation and application of these rights, making it clear that it would not be feasible to interpret the rights in a way that provided individual claimants with a right to demand specific goods and services from the state.

The court was in a difficult position as it had to respect the separation of powers doctrine and could not dictate to the government how to allocate its budgets. At the same time it was required to ensure that the social and economic rights did not remain rights on paper alone, but were interpreted in a way that signalled their enforceability.

This the court did by finding that social and economic rights impose both a negative obligation on the state not to interfere with the existing enjoyment of rights by, for example, evicting somebody from their home or prohibiting a doctor from prescribing available and appropriate medication, and a positive obligation to take reasonably measures to provide more people with better access to social goods and services. Measures would not be reasonable, said the court, if they discriminated against a specific group or if they failed to address the needs of the most vulnerable members of society.

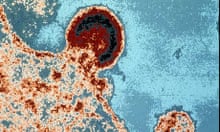

Thus, in a case brought by TAC to challenge the failure of the state to provide ARV's to HIV-positive pregnant mothers, the constitutional court found that a policy that prohibited doctors in the state health system from prescribing ARVs (offered free of charge by the drug company for five years) to pregnant mothers was unconstitutional. It also found that the failure of the state to implement a comprehensive mother-to-child HIV prevention programme was unreasonable and thus unconstitutional.

By the time the court handed down its judgment in the TAC case, the TAC's campaign (which included – but was not limited to – litigation based on section 27 of the constitution) had forced the government to change its policy on HIV and ARV medication. Today the government is committed to provide all HIV-positive individuals who need it (and cannot afford to pay for it) with access to ARV treatment.

The TAC case thus illustrates how social and economic rights can be used by civil society groups to mobilise public support for a worthy cause – even before a court is asked to adjudicate on what will often be very complex legal and moral issues – and that it can enhance democratic engagement and participation.

The constitutional court itself has recognised the potential of social and economic rights to contribute to a deepening of democracy and has fashioned legal tools to do so. Thus, in cases of forced eviction, the court has found that the government acts unreasonably and hence unconstitutionally where it fails to engage in a meaningful manner with those potentially affected by the eviction about the potential eviction and about the provision of alternative accommodation. Government agencies who wish to upgrade informal settlements thus have a duty – imposed by the right of access to housing – to consult those affected and not to impose technocratic "solutions" on them from above.

The South African jurisprudence illustrates that justiciable social and economic rights have enhanced democratic accountability, rather than diminished it – as its critics have claimed.