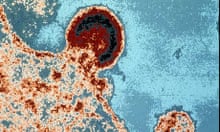

It has an HIV infection rate of 3.2%, placing it above Gambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Senegal, and just behind Nigeria where prevalance is 3.6%. But this is no third-world country – it is the capital city of the richest nation on Earth.

Washington DC's shockingly high place on the HIV infection table is a story of poverty, racial segregation and neglect, which many of those charged with tackling HIV here acknowledge is shameful while insisting it is now being addressed.

But America's record on Aids in its own backyard, in the very shadow of the White House, will be forced into the spotlight later in July when Washington hosts the International Aids Conference, a mighty biennial gathering of scientists and campaigners, who inevitably end up embarrassing the political leaders of the host nation.

It happened in Durban, when Thabo Mbeki was castigated for his doubts over the cause of Aids, and in Bangkok, where demonstrators protested over the jailing of IV drug users. The US has regularly been the subject of criticism – Barack Obama was criticised at the last event, in Vienna in 2010, over cuts in US Aids funding to developing countries. But this time, the event will be on his own turf and demonstrations are already being planned.

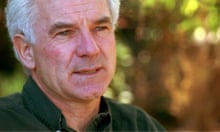

Gregg Gonsalves, a leading Aids activist for over 20 years who now works and studies at Yale, is one of those who is deeply disappointed in Obama, for whom he voted. "He hasn't invested a lot of political capital in HIV. I don't think it is a priority for him. He has cut Pepfar [the president's emergency fund for Aids relief, which helps developing country epidemics] by $200m. He has been an absolute disappointment."

Gonsalves says the continuing infection rates in the US – 50,000 a year – are shocking, and is concerned about the lack of attention to young, black gay men and does not understand why the president does not act to end the waiting lists for drugs. As of May this year, more than 2,700 people across 10 states were waiting for treatment – something that is hard to defend since studies last year showed that prompt treatment made people with HIV less likely to infect others. "This is something he could do in the blink of an eye," said Gonsalves.

What Washington DC, with the highest HIV rate in the US, has in common with Aids-afflicted Africa is a marginalised and impoverished population. As you take the Metro green line south, away from the downtown federal offices and upmarket bars where young and aspiring interns congregate, white people get off and African Americans get on. Before the train crosses the Potomac river, everybody in the carriage is black. Washington DC is recovering from the "white flight" that followed race riots in the 80s, but none of the young Wasps working in downtown DC and laughing in its bars in the early evening head home to Anacostia.

HIV today is not the "gay plague" that hit San Francisco in the 80s. The worst affected are heterosexual African Americans. HIV is rife in places beset by poverty and low levels of education.

That is why Dr Lisa Fitzpatrick, an infectious diseases expert at Howard University, set up a pioneering HIV clinic just over a year ago at the United Medical Center in Anacostia – amongst the homes of the people who need her help.

DC, she says, "used to be 80% black. Now it's more like 60%. It is an area that is disenfranchised. It has high levels of illiteracy and poverty and huge health and social disparities." And Anacostia has greater concentrations of all these social ills than anywhere else in DC.

Most of those who arrive at the clinic on the second floor of the vast plate-glass hospital building have come through the emergency room where they were persuaded to take an HIV test. A positive result is devastating, says Daveda Hudson, the patient navigator whose work is to connect those tested with medical care straight away.

"A lot of them are in a bad state," she says. "Most people cry until they pass out and the they wake up and cry and pass out again. When you come into the ER because you have a sinus infection, it's not what you expect."

Hudson's job is at the heart of what makes this clinic different. She gets the call and heads straight to ER to ensure this collapsed piece of humanity sees Fitzpatrick or a nurse practitioner immediately.

"Just by getting people to walk through the door, you begin a relationship," says Fitzpatrick. It's not 'here is our phone number – call and get an appointment'. Some places still do that."

Then there is a mental health assessment, which will reveal substance abuse and other issues that must be tackled if the patient is to be successfully treated. And it is vital to keep them linked in to the clinic. Antiretroviral drugs keep people with HIV alive and well and prevent them infecting others, but they must be taken regularly or they stop working.

Hudson, helped by other staff such as receptionist Shannon Strong, refuses to let these sometimes difficult and chaotic patents drift away from care. They will call people every day, visit them in their homes, sort out their housing problems, their kids' schooling and their debts. The only way to defeat HIV in these entrenched and deprived places, they believe, is to take on the problems that make people vulnerable.

They still lose some, says Fitzpatrick. "Twenty percent of folks are still lost to follow-up," she says. "For the city it is a serious problem – it is probably as high as 40%." But she too goes the extra mile to pull people in.

"Once I had to meet a patient on the street. I had to explain to him about HIV because he was afraid to come in. He had Aids and he thought he was going to die anyway. Everybody had been calling him. I said I could probably get him to come. He was homeless so I arranged to meet him. It was a busy avenue, so it wasn't unsafe. He showed up a week later at the clinic and he's still in care now. He is doing fine."

David Catania, the outspoken independent chair of DC's health committee, blames previous administrations for failing to tackle the district's HIV epidemic. He tells a shocking tale of incompetence and neglect. "It had been ignored for years and years," he says.

The HIV/Aids department went through many changes of name. "I used to say it was like a witness protection program – it was so humiliated by what it was doing."

When he became chair of the committee in 2005, he said, "There was no epidemiology, because the whole thing was just a shit show." Vacancies were not filled or they were taken by people without the right skills, he claims. "It is what happens when inertia hits a brick wall."

They had no data about the types of people who were becoming infected to inform prevention programs and it was taking nine months to pay providers. "What dollars we did spend got burned in a bonfire out the back. There was one instance where a guy used Aids money to refurbish a strip club. It was just a disgrace." One Inspector General's report after another told them how terrible their contract management was, he says.

"The way we fixed this was in a very Teutonic way, one step at a time," he says. He took over the HIV/Aids department and instituted "a reign of terror". He outsourced the epidemiology to George Washington University and he believes they now have the best HIV data in the country.

They show a drop in the death rate from Aids and the numbers with HIV progressing to Aids. He brought in a major testing programme in the community and 100,000 people are now tested every year.

In the jails, people are tested unless they opt out and those with HIV are given continuing care on release. They gave grants and help to non-profits setting up Aids programmes in the poorest parts of the district. The infrastructure that existed was mostly for gay men, who were no longer the majority of those affected or at risk.

He is very proud of what has been done, but he knows HIV will continue to be a very difficult issue for DC. "The big question now is what do we do about this population of 3.2%? Every time that number plays it is a horrifying number. The only way to get that number down is for these people to die. The good news is that we have 3.2%. If we were another place that didn't take care of these individuals, we could quickly have a smaller population. They would simply die and we could start over.

"It is going to be unbelievably high for a long time. It takes some explaining to the poepulation – to say when things fell apart and we abandoned our responsibilities, we contributed to the epidemic."

He knows Aids activists will be demonstrating in the streets of DC in July. "They often believe the solution is simply more money," he says. "It is not about more money. You can burn money in a bonfire as we have done in this city. It is a shortcut and it is a kind of cartoon version of health."

If Washington has a grip on its epidemic amongst poor African Americans in the south it is still inadequately tackled, say campaigners. The waiting list for Aids drugs for those who cannot afford to pay for themselves tells its own story. Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana and Virginia are among the states where people with HIV cannot immediately get the drugs they need to stay well and reduce their chances of infecting anyone else. Some states have lowered the income level at which people become eligible, squeezing some off the lists altogether.

These are people who usually don't have a voice or a platform. The July conference will change all that.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion