Clive was nine years old when he discovered he was HIV positive. The devastating news that his mother, doctors and support workers had spent years preparing to break to him in the gentlest manner possible, was blurted out by a careless receptionist at his local hospital.

"My mum had bought me to see the doctor because I had earache, and this woman just read it out loud from my notes as she was typing my details into the computer," says Clive, who celebrated his 18th birthday last week. "I remember standing there, with my mother's hand around mine, as these feelings of complete confusion and fear washed over me."

Clive credits the medication given to his mother during her pregnancy for protecting him then from her HIV infection. But, he says, something went catastrophically wrong at the point of delivery, and the infection was passed into his own bloodstream.

After that day at the hospital, however, Clive refused to take medication on his own behalf. "I suddenly realised that the pills my mum had been giving me every day – that I had thought were sweeties – were medicine," he says. "After that day at the hospital, I would lock myself in the bathroom when my mum took them out of the cupboard. Or I'd pretend to swallow them, then throw them away."

Clive's resistance to taking medication became more deep-rooted as he grew up. "The medication makes me feel sick – I was sick every time I took it from 10 to 13 years old. Other times, I just don't want to remember that side of me. I want to be normal."

He shrugs sheepishly. "The last time I stopped taking them was because I broke up with my girlfriend and I had other things on my mind." Clive takes his pills sometimes, he says, but then stops for months at a time. "I know I'm killing myself," he says truthfully, but with studied nonchalance. An exuberant teenager, full of life, he laughs at my shock. Pulling his homburg hat to a jaunty angle, he throws a caricatured "oh, poor me" puppy dog stare.

But there's nothing funny about Clive's attitude towards his HIV status. A decade of sporadic adherence to his drug regime has stunted the teenager's growth. It has left him close to death three times, and caused him to develop resistance to a number of the drugs that could have almost guaranteed him a long and healthy life. "I was in hospital again in January," he says, absently drumming a jazz riff on the table in front of him. "But my hospital visit before that was the worst: I got pneumonia after stopping taking my meds. My CD4 count [cells that help fight infection] was down so low that I was basically dead."

There are around 1,200 children like Clive in the UK and Ireland: young people living with perinatally acquired HIV, contracted from their mother in the womb, at the point of delivery or shortly after birth, while being breastfed.

They are a hidden group. Fiercely protected by a medical profession that never expected them to grow from babies into children, much less teenagers, they seek to exist under society's radar, to avoid being branded by the stigma that it attaches to HIV. Over a number of months, however, many of these young people – and HIV-positive women who have had children of their own – told the Guardian their stories for the first time.

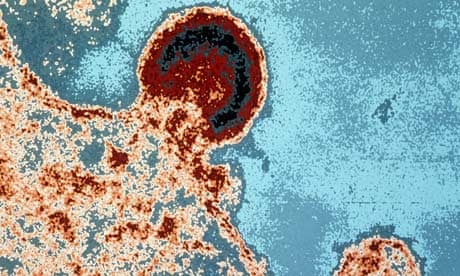

This group of young people are a singular demographic produced in the few years before medical innovation had caught up with real life. The breakthrough in the 1980s of Haart – highly active antiretroviral therapy – gave these children the chance of a normal lifespan. It also reduced the chance of women with HIV passing the disease on to their babies from around 20-30%, to under 1%. Today, says Pat Tookey, who manages the National Study of HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood (NSHPC), the comprehensive, anonymised surveillance of all obstetric and paediatric HIV in the UK and Ireland, there is "a vanishingly small chance giving birth to an HIV-positive baby, if medication is taken from the point of conception and all interventions are followed". "Thanks to the fact that an HIV test is routinely recommended to all pregnant women during their antenatal care, most with HIV are diagnosed in time to take up interventions," she says.

But there was a time lag before Haart reduced the likelihood of transmission between mother and baby so dramatically, and when infected babies were still being born. The seismic shift that happened in these few years was that these HIV-positive babies were, for the first time ever, being born into a world where they were able not just to survive, but to thrive.

"In earlier days, most babies with HIV had a short life and our task was to make the quality of that life reasonable," said Diane Melvin, a consultant clinical psychologist at St Mary's hospital in London. "We never expected these babies to live. They were certainly not expected to survive adolescence."

But that is exactly what they are now doing. Of the 1,200 children born with HIV and living in the UK and Ireland today, just 60 are under four years old. Around 400, in contrast, are aged between 10 to 14, and another 300 are between 15 and 19. Contrast this to the 1980s, when the first infected babies were born. "There was no treatment in the early days," remembers Tookey. "The babies used to turn up with a symptomatic disease and die."

For the first time, doctors are daring to hope that children born with HIV can have a normal life expectancy, provided the drugs work and any issues around resistance are solved. "But this is just an assumption," warns Tookey, "We can't be sure of the future because the virus is good at developing resistance to specific drugs, and none of these children have ever lived into middle – or older age."

Despite medical caution, however, the first cohort of teenagers born with HIV shows every sign of rude health. In what must be the most under-celebrated triumph of modern medicine, in the last two years, the oldest survivors of childhood HIV have grown into young adults.

It is a group that comes in all shapes and sizes: some have problems, some are doing well, some are even starting on their own families. What they all share, however, is the desire to live as normal a life as possible.

"Society forces me to live two lives, one of which - the one where I'm honest about my status - I have to keep completely secret from the other one," says Clive. "It angers me that HIV is considered such a dirty thing by so many people. Why are people more sympathetic to those with cancer than those with HIV? It's partly because I have to live this life of shame and secrecy that I find it so hard to take my meds."

Other young people admit that the stigma of their disease exacerbated their teenage predilection to risk-taking behaviour. "From the age of five to 17, I had to take 23 tablets a day, and I had to do it in secret because of the ignorance in school and society as a whole," says Pauline, now 24. "I got to a point where I had just had enough. I just wanted to block HIV out of my life. I didn't take my meds for a year and a half. Eventually, I was ill for four months, then I lost a stone in three days and couldn't get out of bed. I couldn't breath, my heartbeat was crazy. I thought that was it."

Pauline alerted a friend, who drove her to hospital, where she spent a week in intensive care. Pauline, who has a young – and uninfected – son of her own, is now a mentor for other HIV-positive children. Asked about the problems faced by children growing with HIV today, she angrily says that, "from what the young people tell me, the situation around HIV in schools and society in general hasn't improved at all.

"It doesn't occur to people that you can be born with HIV and live a normal life," she adds. "The result is that some of these children go down the same spiral I did and end up in hospital."

Other teenagers with perinatally acquired HIV, however, refuse to let the disease define them. They take their meds and forge ahead, living confident and strong lives.

Cheerfully tucking into cheesecake while describing her plans for the future, Martha makes a claim that is barely believable. "If I could live my life again and not be positive, I wouldn't want to," the 20-year-old announces, giggling at the astonishment - and disbelief - that I fail to wipe quickly enough from my face. "It sounds weird, I understand that," she acknowledges. "But I've achieved more things by being positive than I would have if I had been born negative. It's made me a much more educated person and put some amazing experiences in my path."

Martha reels off a windfall of opportunities that have come to her, courtesy of her HIV status. "I have spoken at three international Aids conferences, presented at three Children's HIV Association (Chiva) conferences, met MPs, been a mentor to other young people born with HIV, and have written magazine articles for Positively UK [a peer-led support group for HIV-positive people across the UK]." She pauses for breath. "If someone offered me a cure, I might take it," she concedes. "But not definitely. HIV is a really small part of my life. I have HIV; HIV doesn't have me."

Even Martha, however, admits that children born with HIV struggle against far greater odds than those growing up with other perinatally acquired diseases. "I'm angry about the stigma in society that makes me have to lie about my status," she admits. "It should be like having a heart disease or high blood pressure. What I want people to know is that we're living normal, healthy lives. We're alive: we were not supposed to be."

The continuing fear and ignorance about HIV in society, however, continues to make it necessary for young people to lead double lives, despite the damage that can it do to them.

A recent survey by the National Aids Trust found that one in five adults do not realise the disease can be transmitted through sex without a condom. Fewer than half believe it can be passed by sharing needles or syringes. Around 10% believe it can be transmitted through kissing and spitting – an increase of 100% since 2007.

The stigma that society places on HIV has another, even nastier knock-on effect: it means that children cannot be told of their diagnosis until they are judged to be able to keep it confidential.

The consequence of this is that unlike other childhood diseases, children born with HIV often learn of their diagnosis after they have already absorbed the fear and believed the lies about the disease that swill around society. The trauma can be deep and long-lasting.

In one comprehensive survey, a third of children with perinatally acquired HIV admitted to having considered killing themselves. There can also be a direct impact on a child's lifelong adherence to medication. And this, of course, affects others: statistics show that young people with chronic conditions are more likely to report three or more than four simultaneous risky behaviours than healthy teenagers, including unprotected sex.

But even for those children who adjust well to their status, taking medication is not simple. Nor is hiding it from others: some young people have to take 12 different pills, three times every day.

It is a programme to which they must adhere with relentless precision. "For treatment to be effective, you need 97% adherence - to within two hours of taking the pill at the same time every day," says Nimisha Tanna, from Body and Soul, a pioneering charity dedicated to transforming the lives of children, teenagers and families living with, or affected by HIV. "It is very important," she adds. "Otherwise the virus wakes up, mutates and can become permanently resistent to the treatment you're taking."

Persuading adolescents to take their treatment seriously, however, isn't easy. Just like any other teenager, their health is not their first priority nor organisation their strongest suit. Clinics dedicated to young adults with HIV are springing up to try to help this group.

But, says Dr Caroline Foster, a consultant in adolescent HIV at Imperial College healthcare NHS trust, problems can occur when such facilities are not available and 18-year-olds find themselves ejected from the paediatric care facilities they have attended since they were born into an adult facility, ill-adjusted to their specific needs."Adolescent survivors of HIV are a new and challenging population," says Dr Steven Welch, a consultant paediatrician at Birmingham Heartlands hospital. "The challenge is that, having got to the stage when we can enable young people to survive with HIV, we can also give them the quality of life to go with it. But this is entirely new territory for us all: paediatric HIV consultants have never had to deal with adolescents, or their parents. And how do we help a young person, for example, who is about to have their first sexual experience but already has a sexually transmitted disease?"

These are challenges the medical profession must surmount, however, because although about 98% of diagnosed pregnant women now take antiretroviral therapy, there are still at least 40 infected babies born in the UK every year.

It happens, says Tookey, for a range of reasons: the mothers sometimes lead chaotic lifestyles or have long-standing undiagnosed infections. Or they get infected during pregnancy, a time when few women would think to use a condom. There are also women who get infected after they have given birth to a healthy baby but while they are still breastfeeding.

"It's probably unrealistic to say we can get that 40 down to zero," admits Tookey, whose study follows all infants born to women known to be HIV-positive at delivery in UK or Ireland. "But we should be able to get it down to 10 a year if we can make sure women have every opportunity to take the test, and if positive, have as much support as they need to enable them to take up the treatment in pregnancy, and avoid breastfeeding."

That would, of course, be a medical triumph - but those living with HIV are equally concerned that there is a social breakthrough too.

It is because society stigmatises HIV with such "vicious ignorance", says Pauline, that she dreads the moment she has to tell her young son about her own infection. "I got pregnant because I was too scared and ashamed to tell the nurse who gave me my 'morning after' pill about my HIV status. I didn't realise that my medication made a difference to how well the contraception would work," she says. "I'm hoping that, by the time my son needs to learn about my status, the stigma will have come down and people will be more comfortable talking about HIV. I'm hoping that by then, we won't have to hide any more. That learning of my status will be the same as telling him I've got any other manageable disease."

She pauses, an elegant young woman with long, immaculately lacquered nails at which she anxiously picks and tugs. "The fear that my son will judge me for having this disease is something I can't begin to worry about now. Why should he blame me for being born sick? Why should anyone judge me for that?"

Names have been changed

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion