“Welcome to the United States”. I glanced at the sign at arrivals in Miami airport, rushing towards border control to queue in the line of returning US citizens and residents. I have never felt welcome to the United States. It took nine years fighting to belong to the “legal permanent residents”, the so-called green card holders. After fingerprinting and facial check, the officer instructed me to follow him to the interrogation room of the border control.

I am a “212”, marked in the computer system as inadmissible. In 1987, the year before I was diagnosed with HIV, the U.S. implemented a bar for people with HIV to immigrate, travel to, or transit through the US. Only with a special waiver, were people with HIV allowed to stay up to 30 days in the US to attend a special event. In April 1989, a Dutch AIDS educator was arrested for several days, when he tried to attend the U.S. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. This led to an international boycott of the US and the International AIDS Conference has not been held in the United States until now . In 1992, about one hundred Haitians with HIV were placed in quarantine in the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay. Thus “criminalization” of HIV had taken place even before the ban was codified into law in 1993.

In 2001, I challenged the system. I am a medical doctor, psychologist, and scientist. The University of Miami invited me as a scientist for a project on positive psychology and longevity with HIV. I applied for a visa, disclosing my HIV status. The officer at the US consulate in Berlin over-rode the ban, stamped an annotation “212(A)1(A)I” in my visa and I received an HIV waiver valid for 20 months. “I have not made that law. I do not discriminate against people with HIV. Go to the country and change the law,” she smiled. Other immigration officers followed her example and renewed the waiver.

However, the visa clock was ticking faster than the movement to lift the ban. In 2007, I had maxed out my time on a visa and applied for a green card. Within one month, US Citizenship and Immigration Services approved my application based on extraordinary ability and national interest in the HIV arena, the HIV waiver pending. The indefinite wait for the immigration interview felt like voluntary prison in the USA: allowed to stay but not to re-enter.

In the interim, George W. Bush repealed the statutory ban. In March 2009, I went full of hope to the immigration interview. To my surprise, the officer declined the HIV waiver. Our entire family was under deportation even though the HIV ban was repealed. On November 2009, two days Barack Obama announced the end of the HIV ban, my HIV-negative ex-husband was deported, based on my HIV status. With the help of the HIV Law Project, I was able to postpone the deportation of the kids and myself. On January 4, 2010 the HIV ban was lifted. Finally, on April 2010, the court decided that the kids and I could stay in the US. I got my green card just in time to attend the International AIDS Conference in Vienna in July 2010.

In Vienna, at the International AIDS Conference, the announcement of the conference in 2012 in Washington felt like a victory. However, it was no victory. “M'am, when was the last time you were arrested?” was the question on my first re-entry to the USA with the green card after the International Conference in Vienna. I am still a 212.

The 212 U.S. Immigration Act labels “Aliens Ineligible for Visas or Admission” and groups people with health-related issues together with people with criminal background. Severe serial criminals, human traffickers, heavy drug dealers, and people involved in terrorist attacks fall in the same category as people convicted of CIMT, which stands for “crime involving moral turpitude”. The concept of CIMT dates back to US immigration law from the 19th century to exclude sex workers, people using illegalized drugs, and people with communicable diseases. The HIV bar is still in place for all people with HIV who (voluntary or not) disclosed their status before 2010, as well as for sex workers and people who use drugs.

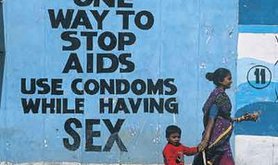

The 212 travel and immigration ban is not only against basic human rights but counterproductive. The criminalization of drug use and sex work has fueled not only a multimillion dollar business of the sex-, drug-, and prison industries but has also escalated into a forty-year old war that has taken many lives. It is time to legalize sex work and drug use to end this pointless war, regardless of international business interests. Sex workers and their allies have chosen to have their own satellite conference in Kolkata during the conference in Washington, because of their 212 status.

Together with AIDS activists and the International AIDS Society, I have tried to resolve the 212 issue. However, the US department of State is not prepared to delete the 212 label from people living with HIV in fear of “secondary reasons”, such as other transmittable diseases or crimes of moral turpitude. Now, the International AIDS Society warns all people living with HIV who have a 212 entry that they may not be able to enter the US. Border Control has the final decision who enters the country.

Every time I enter the US, border control treats me like a criminal. In April 2012, border control wanted to take my green card during the 212 interrogation. He found a so-called secondary reason. I had left the US some days more than 6 months in order to avoid the 212-trouble. When he heard that I had worked for the National Institutes of Health, he gave me another chance to request a re-entry permit in order to pass the next 212 interrogation. Before I returned to Europe, I filed the application including biometrics. In July, re-entry was declined. My fingerprints are not accepted.

Our German organization will not have a ”hub” at the conference, because I was a core media representative. I am not able to present my science at the International AIDS Conference in Washington because I am HIV-positive. Moreover, I am not able to set a footstep back into the US to finish twelve years of research. I have a criminal record because I am open about my HIV status. The stigma made me silent.

This is one of a series of articles that openDemocracy 50.50 is publishing on AIDS gender and human rights in the run up to, and during, the AIDS 2012 conference in Washington DC, July 22-27.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.