The Plague Years, in Film and Memory

What it's like when the worst years of your life get rolled up into an Oscar-nominated documentary

What it's like when the worst years of your life get rolled up into an Oscar-nominated documentary

"Remember when they burnt those people's house down?" Spencer Cox asks.

We are at a reunion dinner for about half a dozen people at a restaurant on the edge of Soho. I haven't seen him since the mid-1990s. He looks unwell. It's late September, 2012. On Nov. 30 we're on a panel together for World AIDS Day at St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center. By Dec. 18 he is dead.

I don't remember, so I look it up when I get back to D.C. In 1987, in Arcadia, Florida, Clifford and Louise Ray's house mysteriously burned to the ground after a court ordered the local schools had to admit their HIV-positive hemopheliac sons, despite community objections. Other families had already been pulling their kids out of the school, which also faced multiple phoned-in bomb threats. The family decided their only option was to give up and leave town.

This was right around the same time homophobia in America peaked, according to Gallup polling of the 1986-87 period. It was Reagan's second term, there were no AIDS treatments (AZT wasn't approved until March 1987), the Supreme Court had recently upheld state laws making gay sex a crime in the June 1986 Bowers v. Hardwick ruling, and 57 percent of those surveyed answered yes when asked if gay and lesbian relations should be illegal. Several states were actively considering quarantine measures for people with AIDS, which is to say, tearing some of their most marginalized and frightened citizens away from the only people who loved them and locking them up with strangers who considered them freaks and pariahs, until they died.

It's no wonder that when Nora Ephron had to cancel a speech at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center of New York in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, in March 1987, leading to playwright Larry Kramer subbing in for her, the gay and lesbian community in what was then the epicenter of the emerging global pandemic exploded. ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, was born out of Larry's call to action.

In July I sat down with a rising Harvard senior writing his honors thesis about ACT UP, and about some of the events I was part of more than 20 years ago. I realized then I'd had only four or five other extended conversations about those years over the past 15. I suppose no one talks very much as an adult about what they did as a teenager, but in truth the reality is more complicated than that. Violence, loss, trauma—all are silencing in their own way. And despite growing up under the banner of Silence=Death—heck, I'm the girl who painted those words onto a lot of the fabric backdrops you can see in the Oscar-nominated documentary How to Survive a Plague, unspooling a bolt of black canvas in my painter father's studio—I have always been reluctant to participate in the age of memoir. What the world sees as talking about history can feel very much to an individual who was part of it—that is, to me—like dwelling. And as a journalist I have preferred to tell other people's stories rather than my own.

"Others would talk about such experiences all the time," a friend IMed me after the September release of How to Survive a Plague, which tells the story of the ACT UP Treatment + Data Committee (of which I was the youngest member) and the Treatment Action Group (of which I was a founding member) and how they worked to transform the drug-approval process and AIDS research in this country, leading eventually to the availability of the only successful antiretrovirals in existence and, once the U.S. and other governments decided to put some money behind drug distribution, the saving of millions of lives around the world.

My only response to that expectation of chattiness is: not if you lived through it. I've written only one reflection on that era previously, for a book a decade ago; it took me two months to squeeze out about 1,200 words, because every time I turned to the subject I either developed such a colossal headache I had to stop, or burst into tears.

Many people who were part of ACT UP have tried to write about it in retrospect, but it took an outsider who was also invested in the story, journalist-turned-filmmaker David France, to bring the story to the mainstream, to the extent that has happened over the past year. France was one of the earliest chroniclers of the epidemic, first in the gay press and later for New York and national media outlets, and a man whose partner Doug Gould, to whom the film is dedicated, died of AIDS in 1992. France's documentary, distributed by IFC and Sundance Selects, has won a slew of awards since premiering in January 2012 in the documentary competition in Sundance, and then in theaters in September. (It's also now available on iTunes and Netflix). It's even been nominated for an Academy Award in the Documentary Feature category.

The movie focuses on three HIV-positive men to tell the larger story of the early years of AIDS treatment activism, when death came quick and violently: Peter Staley, a dynamic former bond trader who in his late 20s was given two years to live before joining ACT UP and undertaking some of its most daring and theatrical actions (if an action involved scaling part of a building or bolting yourself in somewhere with power tools, Peter was likely involved); film archivist and later MacArthur genius award-grantee Mark Harrington, the chain-smoking intellectual force behind T+D on whose amber-screened 286 computer most of T+D's giant technical documents were tapped out; and the late Bob Rafsky, a publicist turned ACT UPper who famously heckled then-candidate Bill Clinton in 1992 and was told in reply a line that would come to define the president, "I feel your pain."

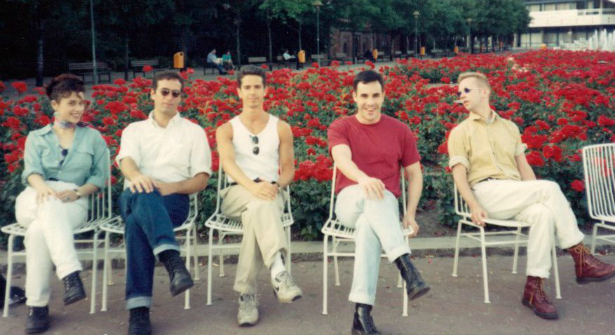

Also featured are activists Jim Eigo, Iris Long, Ann Northrop, Larry Kramer, Gregg Gonsalves, Gregg Bordowitz, Derek Link, Bill Bahlman, David Barr, Spencer Cox, Ray Navarro, and myself. Plus: scientists Emilio Emini, Ellen Cooper, Susan Ellenberg and Tony Fauci, along with an array of activists who, though not named in the footage, will recognize themselves in various scenes, along with their departed friends.

I worked with ACT UP from 1988 through 1991, after which a group of the T+Ders left to start TAG, which Harrington continues to run to this day. I worked with TAG for a couple of years in college, co-founded the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition in 1995, and then left AIDS work entirely in 1997, when I moved to D.C. after graduating from college and fell into journalism. A life as a member of the chorus instead of one of the dramatis personae on the American stage seemed about my speed after what I'd seen; after all, the chorus is always still standing at the end of the play.

ACT UP was the last of the great new social movements of the 20th century, a direct descendent of all that had come before, its members trained by veterans of Stonewall, the Freedom Summer, and the grassroots creators of the women's and gay liberation movements. At its peak, it had a budget of more than a million a year—without a single paid staffer. (In fact, if I recall correctly from my days on the Coordinating Committee, the greatest regular monthly expense was the industrial-strength Xerox machine we rented to produce reports, letters, fliers, and posters.) Independent affiliates took root in more than 100 sites around the world. Roughly 1,000 people came together every Monday night in lower Manhattan in the purest example of democracy I've ever experienced, to argue, plan, cajole and flirt, before breaking for a week in which more than 40 committees and subcommittees would continue the work on everything from neuroscience to HIV prevention to housing policy.

Everything ACT UP did it did analog. It posted posters on actual walls, with wheat-paste mixed in great buckets and slapped up late at night by members risking arrest. People spread messages through phone trees, from their landlines. And when there were protests they were anything but virtual, or done in a flash-mob style. ACT UP believed in training. It believed in planning, logistics, tactics, strategy, clearly articulated and well-researched demands, and, most importantly, it believed in getting results. It was not an outlet for emotion, but a channel for using the unique mix of anger and terror that characterized the times to achieve concrete ends with physical consequences for people in dire straits.

It was group of despised, gorgeous, terrified and terribly, terribly young people who looked death and society in the face and said no, we will not go quietly into that good night. Save us or give us the means to save ourselves. I have never met people since (I'd say before, too, except for me, I was so young, there wasn't much of a before) so committed to staying in the land of the living. It was an assertion of basic human dignity and that fierce will to live in the face of hatred and the neglect that was its vicious stepchild. And it helped change the drug approval and research process in this country, giving the entire world medicines that have saved millions of lives years before they might otherwise have been available or discovered. That is a fact.

The movie tells an incredibly powerful narrative about a micro-community within ACT UP and the larger movement for AIDS treatment research, which itself was a micro-community within a global network of people fighting on behalf of people with AIDS. It is not the whole story of AIDS activism's early years (and obviously, the work continues), but it is the best narrative of this part of the story I have seen so far, and the only one that tells this particular tale. Also out in 2012 was Jim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman's United in Anger: A History of ACT UP, which combines original footage with interviews from their ACT UP Oral History Project, to tell a slightly different set of stories about the group, though with less narrative panache and more chronological fidelity. If I have any criticism of either film it is that the decision to tell the story of AIDS activism through original footage, while giving the films a raw and powerful you-are-there perspective, privileges the protests over all the other sorts of work the group did that was left unfilmed, either for privacy reasons or because just not very visually interesting. (Jim Eigo has raised the same concern about how ACT UP gets historicized.) Neither movie uses still photos with voice-overs, for example—a traditional approach for documentaries, and one used liberally in David Weissman's We Were Here, the 2011 film about the plague years in San Francisco as told through the stories of five people who lived through the horror in the other major epicenter of the epidemic in America. And yet another angle on the larger story is told through Jeffrey Schwartz's movie Vito, about film scholar and gay activist Vito Russo, who was one of the dozen founders of ACT UP. The reality is that no single film can encompass the full story of a formally leaderless group that had thousands of members. And this is just the first wave of movies about it.

That said, it is the (expertly edited) original footage in How to Survive a Plague that provides its biggest emotional wallop. There are moments in it that just slay me, because those were not just my friends but in some important way the people who raised me. The stricken look on Eric Sawyer's face at Mark Fisher's funeral. Bob Rafsky dancing with his daughter Sara—now a grown woman who I'm delighted to say has become a friend through this film. My friend Mark Harrington flirting with the camera while lighting a cigarette, the epitome of '80s East Village cool. Ray Navarro after he'd gone blind and deaf, trying to imagine life for himself in that state, not long before dying at age 26. What Peter Staley, making his first national media appearance, said to Pat Buchanan on Crossfire. The 1992 Ashes Action, which I did not even know had happened until I saw the movie, in which people threw the ashes of their loved ones on the South Lawn of the White House. Really, there needs to be a plaque on that part of the White House fence; it is the final resting place for so many, including for one of ACT UP's founders, Ortez Alderson, a gay black community activist from the South Side of Chicago. And the music, Superhuman Happiness performing the songs of Arthur Russell, is incredible.

ACT UP worked because America worked. I'm not sure we expected that, even as we hoped for it. It taught me that everything that is marginal and powerful in American life eventually becomes central, part of the great churning from edges to mainstream that is one of the most underheralded but deep-seated patterns of our politics. That politicians only ratify social changes that start elsewhere, while true leadership comes from the grassroots, and the people. And that whoever has the most energy in any political battle usually wins. ACT UP was a fireball of energy.

In the movie I say that TAG was one of the little mercury balls that flew off the main body of ACT UP. What I meant is that ACT UP gave rise to a lot of different things, of which TAG was only one. Housing Works was founded by five ACT UP members as an outgrowth of the work of the Housing Committee. The legalization of needle exchange in New York state and the harm reduction philosophy grew with the help of ACT UP actions. Queer Nation beaded off to focus on gay-rights questions full-time. From the Bronx to Brooklyn, New Jersey to Maine, Albany to Washington, D.C., ACT UP New York worked in coalition and in solidarity with a wide array of groups on HIV-prevention, treatment, and access to care even as it kept up so steady a program of zaps and actions the New York Times once labeled it "ubiquitous."

The first time I saw How to Survive a Plague on the big screen was at its premiere at Sundance in 2011, where it was a selection in the documentary competition. I was a wreck the next day. To say that the movie brought up a lot would be an understatement. Maybe one day I'll write the story of my life, and how I went from being a high school drop-out who left home two months after turning 16 to a magna cum laude college graduate and journalist after a years-long interlude devoted to fighting pandemic death. But I doubt it. ACT UP made me and then ACT UP unmade me; it taught me to write and argue and speak and know that the world is full of exceptions and you just have to decide you are going to be one of them. But life on the other side of the knowledge of life and death meant also that by the time I was 21 I had seen and felt and experienced so much I became convinced that if I had to process one more thing —one more awful thing—I would just keel over and die. I had reached my limit, which might have been lower than that of some of the group's other members, because I had no well of fortitude built up over time to fall back on, because, again, I'd barely had any "before" years. What I did have though was health and youth and what too many of my friends did not—a future. And so at a certain point I made a decision to go on with my life. Because I could. But also because I had to. As Ingrid Bergman famously quipped, "Happiness is good health and a bad memory." Most days I do not at all mind that I have forgotten as much as I have.

But on that January day when I was remembering too much, I took impromptu refuge from the social whirl of Park City in festival mode within the Mormon Family Center on Main Street in an effort to keep my silent and unstanchable tears out of view. There a kindly older woman let me use the computers intended for genealogical research in their public basement lab to start what I hoped would be a piece about the movie but that over the weekend after my return from Utah turned into what you see below. I used the Mormons' Ancestry.com registry to confirm the birth and death dates of the members of ACT UP New York who did not make it, as provided by former member Debra Levine and others on the group's Facebook alumni group in a thread provoked by her and the then-impending 25th anniversary of the group's founding. Along with the names was unleashed a torrent of pent-up grief and bittersweet memories. It was a relief to find others had had as much difficulty over the years talking about the mass death experience as did I. The collective mass death experience. Because every AIDS organization that existed in New York in those years has a list like this one. And every person who lived through those years in certain communities knows they can compile a list like this one, if they have not already, and if they can bear it.

There was a time when we were all alive together.

1988

Steven M. Webb, 32 (suicide)

Joe Teti

William McCann

Frank O'Dowd

Michael (Max) Navarre, 33

1989

Griffin Gold, 33

John Bohne

Michael I. Hirsch, 34

Kevin Sutton, 27

Costa Pappas

Steve Zabel

Brian (Allen) Damage

Barry Gingell, 34

Bill Olander, 38

1990

Clarke Taylor, 46

Keith Haring, 31

David Liebhart, 39

Ortez Alderson, 38

Vito Russo, 44

Kevin Smith

Raymond (Ray) Navarro, 26

William Oliver Johnston, 38

1991

Adrian Kellard, 32

Phil Zwickler, 36

Rick Damiata, 42

Jeff Gates

David Lopez, 28

Anthony Ledesma, 29

Jerry S. Jontz, 35

Dennis Kane, 37

Tim Powers, 33

Daniel Connor

Iris de la Cruz, 37

Alan Robinson

Jay Lipner, 46

Mark J. Fotopoulos, 35

Lee Arsenault

Allen Barnett, 36

1992

Donald P. Ruddy, 38

Martin (Marty) Robinson, 49

Charles Andrew Barber, 36

David Wojnarowicz, 37

Mark Lowe Fisher, 39

Jake Corbin (John Avino)

Luis Salazar, 27

David Serko, 32

Scott Slutsky, 37

Katrina Haslip, 33

Tom Cunningham, 32

John Henry Wagenhauser

Rich W. Korotchen

Alan Contini

Cliff Kali Goodman

1993

Carl Sigmon, 66

Bob Rafsky, 47

Robert Garcia, 31

Tim Bailey, 35

David E. Kirschenbaum, 30

Jon Greenberg, 37

Chris DeBlasio, 34

Michael Callen, 38

Yolanda Serrano, 45

Andrew S. Zysman, 38

1994

Clint Wilding Smith, 40

Gary Clare, 32

Mark Carson, 40

David Roche

Michael Morrissey

Aldyn McKean, 45

James (Jim) A. Serafini, 49

Robert Rygor, 40

Robert Massa, 36

David B. Feinberg, 37

Joe Franco

Casper G. Schmidt

Jay Funk, 35

1995

Lee Schy, 35

Tony Malliaris, 33

Bradley Ball, 34

Andy Valentin

Larry Gutenberg, 46

Robert D. Farber, 47

John Cook

Rex Wasserman

Steve Brown

Kiki Mason, 36

David Bolen, 31

Todd Moore

Michael Slocum

1996

Brian Weil, 41

Rand (Randy) Snyder

Mark Simpson

Howard Pope, 35

Billy Heekin

David Petersen, 54

1997

Wayne Fischer, 39

1999

Rodney Sorge, 30

William Wilson, 51

2000

Stephen Gendin, 34

2001

Robert S. Jones, 47

2002

Frank Moore, 48

2003

Evan Ruderman, 44

2004

Keith Cylar, 45

Rick Mount

2005

Brenda Howard, 58

(cancer)

2006

Juan Mendez, 41

2007

James (Jim) Lyons, 46

John H. (Michael) Gilbert, 40

Eric Schweitzer, 63 (pneumonia)

Anthony J. Seibert, 36

2008

Sydney Pokorny, 42

2009

Rodger McFarlane, 54 (suicide)

Robert Hilferty, 49 (suicide)

2010

Harry Weider, 57 (car accident)

2011

Herb Spiers, 65

2012

Richard Krulikowski, 61

Spencer Cox, 44

There are others whose dates of death remain unknown.