In our era of social media saturation, suggesting that technology has transformed intimacy would not be a radical idea. From facilitating political communities to online dating, technology presents us with a number of exciting opportunities and anxieties.

Let’s take Grindr as an example. For same-sex attracted men, myself included, it has become the smartphone symbol for the possibilities of organising sex, friendship and relationships with the tap of a screen. The product markets this quite clearly:

“Grindr is quick, convenient, and discreet. And it’s as anonymous as you want it to be.”

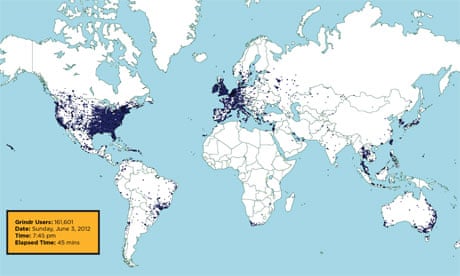

It also has millions of users worldwide. Whether you are reading in a library or lying in the park, everywhere you go with your phone becomes a site of sexual possibility. Bodies are conveniently cropped, filtered and framed for consumption.

In our haste to use the platform, though, we often ignore a critical question: what emotional work is involved when seeking intimacy online?

Emotional labour is not a novel concept. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild refers to it as the work involved in managing our feelings and how we express them. We do this everyday. We do it when we manage (not always successfully) our feelings of anxiety at a bourgeoning relationship, or when we are asked to feign interest in a conversation that bores us.

Online spaces makes this much harder to navigate since we oscillate between disparate feelings in a confined space of time. From the moment I sign on to Grindr, these bodies are presented as assortment of thumbnails, ordered in terms of geographical proximity. Sorting through each profile makes me feel like I’m a kid in an adult candy store: “window-shopping” my way through, hoping to find the right guy to fit my current mood. I could just be after casual sex or be looking to find a romantic partner. It could even be both! This is best illustrated by the pop culture phrase: “looking for Mr Right or Mr Right Now.”

I can “star” our favourite users and segment our conversations. I’m in control of who I respond to, how quickly I respond, and the nature of the conversation I am having. I can tap incessantly on one screen, sending photos to a guy looking to “hook up now” while scrolling through to a conversation with a friend about where to have brunch on Sunday. Then I return to another conversation with a potential boyfriend to reflect on how amazing our previous date was and to eagerly organise our next one.

The first conversation titillates me as I imagine the prospect of immediate sex. The next puts me in a relaxed state of mind as I talk about my favourite local cafes. The last one generates longing or hope as we converse about sparking a relationship. Meanwhile, all this textual intercoursing happens within the space of minutes. Our physical, intellectual and emotional capacities go into overdrive. It can be quite exhausting.

With this in mind, it probably comes as no surprise that many Grindr users have deleted and reinstalled the application several times. With the labour and time demands of talking to so many people, Grindr becomes an intimate commitment of its own.

Then, of course, there is the anxiety over finding ways to limit (or not) how you use it. Do you continue to use it when you have a monogamous partner? How do you express your desires in ways that do not marginalise others? Do you keep searching for more and more people to talk to, or do you invest time in cultivating attachments to those you have already formed a connection with?

The recent web series The Grindr Guide shows us that the possibility of pleasure or romance comes with its own kinds of intimate anxieties. Some people feel hopeful after going on a stimulating date, only to then be disappointed to see their date on Grindr immediately after. Relationship surveillance takes on a problematic dimension: we can now monitor the movements of the people we are dating, or just talking to. We can see when they are online, where they are, and what they are looking for. Our desire for surveillance feeds on this anxiety loop.

Grindr makes us work through a smorgasbord of feelings, often within incredibly short spaces of time. We cruise. We talk. We share photos. We meet people. We do that in a myriad of combinations.

It is important to celebrate the capacity to form online intimacies – but we need to seriously account for the emotional labour that is involved in pursuing them. While people say nothing worth having comes easily, we need to ask ourselves: are we willing to pay the emotional price for it?