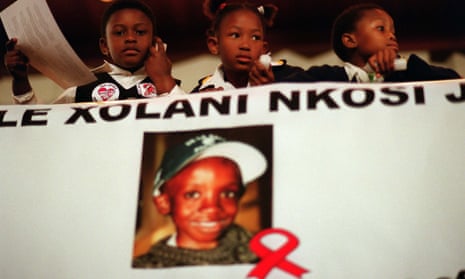

Sixteen years ago, an 11-year-old boy and a judge alerted a shocked world to the terrible reality of Aids in Africa, where hospitals were overflowing with the dying and children were orphaned.

The international Aids conference, held in 2000 in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal – the world’s worst-hit region – was billed as a scientific meeting. It became a week-long, vibrant, impassioned, singing, dancing, drumming and marching mass rally. Scientific neutrality disappeared as researchers became campaigners too.

The cry was for drugs to save lives. It was too late for Nkosi Johnson, the boy who spoke at the opening ceremony. He died the next year. Judge Edwin Cameron stunned his native South Africa by declaring he was gay and HIV positive, and said it was iniquitous that he could buy drugs from Europe or the US to save his own life while his countrymen and women died in their thousands. Nelson Mandela called on the world to act.

Their calls were heard. Campaigners, in collusion with generic drug makers, brought down the price of a three-drug cocktail to suppress the virus and keep people well, the cost dipping from $10,000 a year then to $100 (£76) today. Last week the conference was back in Durban, with 17 million people on treatment. But it’s not over. Far from it. There is a real possibility that Aids will re-emerge as the mass killer it was at the turn of this century.

There are about 38 million people with HIV, so more than 20 million are not yet on treatment. About 2 million more get infected every year. Antiretroviral drugs not only keep people well but also stop them being infectious. The World Health Organisation now advises that anyone with HIV should take drugs as quickly as possible, not just for their health but to protect their sexual partners. In September, South Africa will introduce test and treat.

However, this year’s conference heard disturbing news from researchers at the Wellcome-funded Africa Centre for Population Health in KwaZulu-Natal, which has been trialling test and treat in a population where nearly one in three people have HIV. They found that while most people agreed to be tested by health workers visiting their homes, only half of those who were diagnosed with HIV then went to a clinic to get the treatment that would stop them infecting their partners.

Test and treat

In Eshowe, a town of 14,000 people set among rolling hills and sugar plantations, Médecins Sans Frontières has been pioneering testing by health workers who go door to door. MSF has also opened testing booths next to the butcher’s and by the taxi rank, where working men pass by on payday. They have found the same thing as the researchers in KwaZulu-Natal. They can get high proportions of people tested – but not to the clinic to get the drugs.

“We give them referral letters to the clinic. Then you find they don’t go,” says Babongile Luhlongwane, who walks miles every day on rough tracks with her kit in a backpack to reach those who live in this rural community. “Last Monday I had three men who tested positive. Two went to the clinic. The other said he didn’t have time.”

Dr Carlos Arias leads MSF’s initiative to set up monthly clinics on sugar plantations, testing workers for HIV and delivering medication. He says they see people with Aids who have virtually no immune system left.

South African guidelines say people should be treated when their CD4 count – a measure of the strength of their immune system – drops below 500. “We see CD4 counts of less than 100 – CD4s of five or six,” he says. A serious infection would kill them. He tells of one man who arrived with a CD4 of 13 but did nothing about it. Two years later he was tested again and had a CD4 of 8. That means the virus in his body will be rampant and he will be highly infectious to a sexual partner. “HIV prevalence here is enormous,” he says. “In KwaZulu-Natal, among women aged 15 to 29, it is 56.8%.”

The Africa Centre trial in northern KwaZulu-Natal compared what happened in 22 clusters of 1,000 people: half were randomly allocated to test and treat, half told they would be given drugs when their CD4 count dropped below 350 (500 when government guidelines later changed). The trial set up a mobile clinic in each of the 22 clusters.

The trial investigated whether immediate treatment led to a drop in the numbers becoming infected. The answer, to their dismay, was no.

“Disappointingly, we found no difference in the number of new infections between these two randomised sets of clusters,” says Deenan Pillay, director of the Africa Centre and professor of virology at University College London.

Sex in the cities was an issue. People were travelling away from home into Durban and Johannesburg a lot more than expected, and having sex there. But more problematic are the social and cultural mores that have long beset HIV response in Africa. Far fewer men went to the clinics for treatment than women. “It is a hierarchical society. It is about being seen to be positive. There is stigma associated with it,” says Pillay.

He has been working with this community for more than 10 years, he says, and saw the huge change when people stopped dying. “Treatment was first used for people who were very ill and dying – and they lived. Now we talk about people who appear well and look well and you are asking them to medicalise themselves, to go to this government clinic where you have to queue up all day and you see other people you know there.”

Pillay thinks more must be done to target the sugar daddies or “blessers” – the older, working men who give gifts and money to impoverished young girls in exchange for sex. About 60% of new cases are women. “It is horrendous. In our setting, a 15-year-old girl today has an 80% chance of being infected in her lifetime,” he says. At antenatal clinics where pregnant women are all tested for HIV, half are positive.

The government has launched a campaign telling young girls not to sleep with older men. But, says Pillay, “the real problem is the men who are not being tested and treated”.

“It is a complete crisis. The message of the conference is that there is all this hope – and it is not sustainable.”

Cost is a huge and growing issue. If test and treat worked, it would slash the bills by preventing new infections. But that assumption now seems premature and funding from donors has dropped for the first time. A report by the Kaiser Family Foundation and UNAids says they gave $7.5bn last year, compared with $8.6bn in 2014.

The drugs bill is going to rise dramatically, not just because of the increase in infections and the fact that everybody must take antiretroviral therapy for life, but also because resistance is spreading to the basic three-drug combination available in Africa for as little as $100 a year. Hospital beds are once more taken up by Aids patients whose treatment has failed. Africa cannot afford the newer drugs available in Europe and the US.

MSF has found resistance levels to the basic combination of 10% in its South Africa projects. There has been worse news in other parts of Africa. A study covering Kenya, Malawi and Mozambique found 30% of people on second-line treatment, which costs at least $300, were resistant. The lowest cost of a third-line drug regime – or salvage therapy – in Africa is $1,859 a person annually.

“I think we are seeing the tip of the iceberg,” says Dr Vivian Cox of MSF. “A lot of countries are not doing routine viral load monitoring in the first place. They are moving towards it and then you can imagine what they will find.”

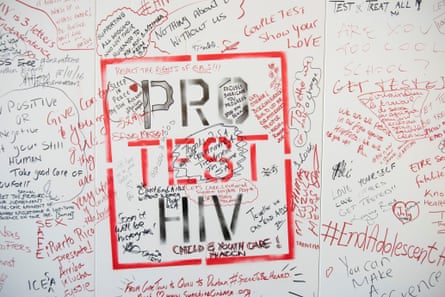

Youth focus

Nobody at this year’s conference was talking about the end of Aids, as they were only four years ago when the conference was held in Washington DC. Bill Gates expressed real concern. If it is difficult now to treat and prevent HIV infections, he said, the demographic bulge could make things worse.

“If we only do as well as we have been doing, the number of people with HIV will go up even beyond its previous peak,” Gates said. “We have to do an incredible amount to reduce the incidence of the number of people getting the infection. To start writing the story of the end of Aids, new ways of thinking about treatment and prevention are essential.”

A vaccine is still a long way off. Pre-exposure prophylaxis works for the partners of people with HIV in the global north. Taking an antiretroviral drug guards them against infection. But that looks very hard to implement for young women in Africa who barely own their own bodies and could face accusations of either having HIV or being a prostitute.

There are brave attempts to change behaviour and the subservience of women and girls. Actor Charlize Theron is funding projects to educate, help and support young people. MTV’s Staying Alive Foundation is attempting to reach young people through its mass media campaign Shuga, sharing the sexual lives of more affluent young Africans. After two series in Kenya and two in Nigeria, the fifth will be filmed in South Africa.

Surveys carried out in South African schools to determine the issues facing 14- to 20-year-olds before the new series offer a glimpse of the dangers they face. A third of girls said a girl does not have the right to ask a boy to stop kissing her. A quarter of the boys said they had “sexually forced” someone. A fifth of the girls said they were sexually active and most of those had been forced into sexual activity at some point.

“The figures point to 86% of sexually active girls experiencing being sexually forced by their boyfriends,” say the researchers. “These figures … reflect a need to understand what is going on within heterosexual relationships and the experience and position of risk within those relationships. It also calls for HIV prevention efforts to help build safe and supportive norms within relationships.”

Of the girls among the 3,000 students surveyed in three provinces over two years, 15% said they had been pregnant – which equates to 70% saying they are sexually active. Nearly half the young people – 46% – said a young couple who went public about one of them becoming HIV positive would be openly judged and 4% thought they would be physically harmed. “This indicates the fear-filled environment South African young people are still growing up in when it comes to HIV,” says the report. “Fear keeps people silent and silence feeds everyone’s risk for HIV and for not getting the care and support they require to address HIV infection.”

Research is showing that Shuga does have an impact on young people’s behaviour. “Where we see behaviour change work really well is when the audience see their own lives reflected in the storylines,” says Georgia Arnold, executive director of the MTV Staying Alive Foundation, who says she wants to get a DVD to every one of the 6 million high school students in South Africa.

“We’ve had a recent World Bank study that was done on … series four in Nigeria. It was a random, cluster study of 5,000 young people and what it proved was that if you watched MTV Shuga you are twice as likely to get tested for HIV.”

Behaviour change could stop the epidemic – although it is not doing so in Europe or the US – and initiatives could help improve young people’s lives. But it is difficult and slow. Aids will be with us for far longer than anybody used to imagine.

Professor Peter Piot, the first head of UNAids and director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, says the biggest challenge is keeping people from being infected. “It is as if we’re rowing in a boat with a big hole and we are just trying to take the water out. We’re in a big crisis with this continuing number of infections and that’s not a matter of just doing a few interventions.

“We will not end HIV as an epidemic just by medical means. People are not robots. Sex happens in a context. It is about power. Southern African girls and young women are infected by men who are much older than themselves. It’s about poverty. It’s also about a culture of machismo. There are also gay men all over the world who are discriminated against and underground, and there’s no way you can prevent infections if something is underground.”

He believes that it was a mistake to foresee the end of the epidemic a few years ago. “I don’t believe the slogan ‘the end of Aids by 2030’ is realistic and it could be counter-productive. It could suggest that it’s fine, it’s all over and we can move to something else. No. Aids is still one of the biggest killers in the world.”