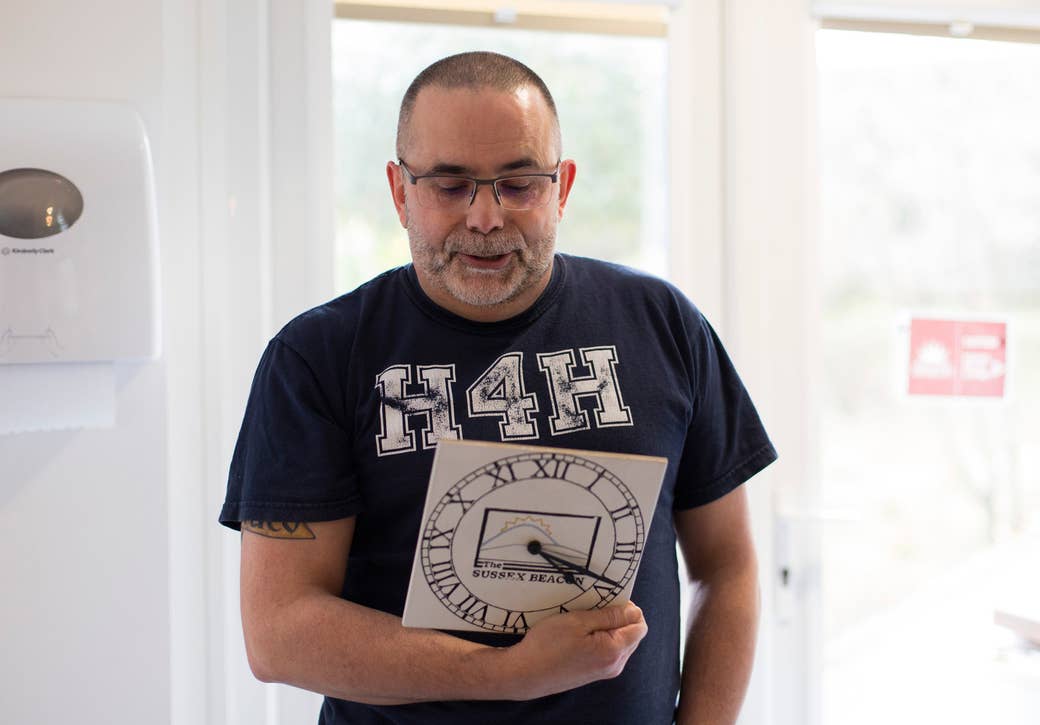

A white clock hangs up near the ceiling of the quiet, light day room at the heart of the Sussex Beacon. Sitting on a nearby sofa is a man in his fifties who stands suddenly, removes the clock, and turns it over. On the back it says: “Tim Smith 1996”.

He is Tim Smith. He made it in a workshop when he first came here as a patient 21 years ago. It was after he lost the man he calls his soulmate, and when all that was certain was that he would soon join him. There used to be lots of workshops here: encouraging the patients to focus on arts and crafts, a distraction from the inevitable. The clock is ticking again now, not on Smith’s life – the pneumonia never won – but on the centre that saved him again and again.

It is a Friday afternoon when the Sussex Beacon’s chief executive, Simon Dowe, and clinical services director, Jason Warriner, show BuzzFeed News around. The centre sits right up on a hill on the outskirts of Brighton – a building for the forgotten. The wind swirls around the courtyard, blustering over the curves of the South Downs as it rolls out to the horizon.

They used to lose four people a week here, when AIDS cut through the town like a flashing blade. The basement was a morgue. Today, deaths are a fraction of what they were in the early 1990s when the purpose-built centre opened to offer dignity to men and women facing the end.

But people still die here, looking out at life below, cradled by staff whom the patients call a family. No one calls it AIDS any more. And those who survived the epidemic are often marooned, cut off from loved ones or employment; life severed by illness and loss.

The Sussex Beacon still shines, tending to the sick, struggling, and dying, but cuts to funding could soon mean the light goes out – cuts that are fanning out across the HIV sector.

It is one of only three facilities left in Britain that provide specialist residential care for those with the most complex conditions resulting from the virus. And it is the only one outside London that combines inpatient care with a day unit. The fight to save the Beacon has begun.

In the week that BuzzFeed News visits the centre – a charity funded partly by the NHS and the local authority – new data is revealed by the National AIDS Trust, following a series of Freedom of Information requests: Despite more than 100,000 people still living with HIV in the UK (a number that increases by several thousand each year) and approximately 300 HIV-related deaths per annum, expenditure by local authorities on HIV support services in England was cut by 28% between 2015/16 and 2016/17. In Wales it fell by 34%.

Some councils outside of London slashed funding to zero. NAT’s chief executive, Deborah Gold, described these reductions as “extremely alarming”, “short-sighted”, and “dangerous”. She accused the NHS of not fulfilling its duties, of leaving the vulnerable exposed.

The standard of service provided at the Sussex Beacon is not in doubt – the Care Quality Commission rated it “outstanding” last year. The doubt that does echo around this place, however, raises cold questions about our time: Are we still prepared to afford the best for those who have endured the worst?

As the afternoon unfolds, as Tim Smith and the staff talk, what emerges is that there is more to his story than first appears – and more to the story of this centre’s fight for survival.

The Beacon was built in 1992 on the site of an old tuberculosis hospital. TB patients were sent up here to be away from people, so they couldn’t infect others, and so the hillside air could cleanse their lungs. Out of town, the patients were also out of sight. As we move from room to room, parallels of such invisibility return and return.

Upstairs is the inpatient unit. Dowe, the CEO, and Warriner, the clinical director, open a door into a currently vacant room. It is compact but pristine, with a hospital bed, a bedside table, and a balcony overlooking the pretty, well-kempt garden – volunteers tend to it.

Each inpatient has their own private room, with bathroom and balcony, explains Warriner: They can look out but no one can see in, in order to “maintain privacy and dignity”. There are 10 rooms.

At any one time they normally have about eight rooms that are occupied, he says – full capacity would make it impossible to do deep cleans, or to enable emergency cases to be admitted.

“We take referrals from local GP services, social services, mental health professionals,” says Warriner – as well as from the local hospital. The reasons for a referral, he adds, are numerous and often pertain to the interplay of medical, social, and psychological issues facing people with HIV.

While most with the virus now live normal, healthy lives, enjoying – thanks to modern antiretroviral drugs – the same life expectancy as HIV-negative people, Warriner says that there are about 10% struggling, with everything compounded by stigma. These are the people who come through their doors.

“Some have brain-related impairment, cognitive impairment, or the early signs of dementia,” he says. Left untreated, which was always the case until 1996 when combination therapy (the first effective treatment) arrived, HIV enters the brain and at an organic level can trigger cognitive problems as well as depression.

We walk through to the main medical room; there are oxygen cylinders, an ECG machine, full resuscitation equipment, a defibrillator, and all the HIV drugs.

Other inpatients, he explains, are treated for an array of different cancers, many of which are more prevalent in HIV-positive people. “They might be starting chemotherapy or radiotherapy,” says Warriner, and so the Beacon looks after them with “initial support to keep the HIV stable so they can continue with the cancer treatment”.

As people with HIV age, a range of other related health problems arise more commonly than with HIV-negative people, and at a younger age. Combined with the grim side effects of early versions of antiretrovirals, some of which were highly toxic and insufficiently tested in trials, long-term survivors battle on several fronts: from organ damage and bone density problems to high blood pressure. So, says Warriner, there are patients at the Beacon with “a lot of conditions around cardiac care, and diabetes” as clinicians continue to fire-fight.

“We’re learning every day about how HIV affects the body,” he says. “We’ve got the highest cohort of HIV outside London and a large number of those ageing with HIV.” Brighton is known for its prominent LGBT population and is particularly popular among older members of the community.

Psychological and substance-abuse problems also bring people to the Beacon for treatment, says Warriner. “A lot of people thought they’d be dead – if you got diagnosed in the 1980s you would see your friends dying, your partners, and the big question is: Why did I survive? There might be post-traumatic stress, and feelings of guilt.”

Some patients’ are suffering psychologically, and in turn physically, following changes to the benefits system over the last five years, he says. And some come for medically assisted drug and alcohol detox.

As well as nurses who work at the centre, there is a doctor, a mental health nurse available, and access to local counselling services. The first cut that came recently, however, saw the end of an onsite psychological service for cognitive behavioural therapy.

But the centre is still receiving occupational therapy and physiotherapy services and, crucially, is still able to offer end-of-life care. Sometimes this can mean a stay of several weeks.

“People who choose to come here [to die] do so because they feel safe here because they’ve accessed services here for years,” says Dowe.

“We had a patient here last year and his wife had died and he didn’t want to die on his own, so we had a member of staff with him all the time,” adds Warriner. “When he died there was a member of staff holding his hand.”

They try to make hospice care as individual and personal as possible. “Another patient loved gin and tonic and every day he got his gin and tonic,” says Warriner. “It’s staff responding to things like that, and understanding. That is a good death for someone.”

But everything comes down to money.

The 10 residential beds are funded separately, by different clinical commissioning groups (CCGs). The problem now looming over the operation is the changes to funding made by some of those CCGs. So for example, says Dowe, last year, the three CCGs in East Sussex stopped funding one bed in a constant block-booking, and switched to a night-by-night basis.

But, says Dowe, even if a bed is empty you need the same staffing levels, and “they capped it at half the level we had previously. We had £50,000 cut from East Sussex. And we’re still running a 10-bed inpatient unit whether they’re paying for it or not – and that’s when it becomes unsustainable.”

A spokesperson for High Weald Lewes Havens CCG tells BuzzFeed News that "demand for the beds for people from East Sussex has been low... and in 2015/16 East Sussex patients used just 20% of contracted bed nights. It is vital that we make the best use of our resources.”

And a spokesperson for the other two East Sussex CCGs tells BuzzFeed News: “As public bodies, we have to ensure our funds are spent in the most effective way for all of our population” and that “£50,000 cap is a guide, and where necessary we will fund beyond that amount to ensure we are paying the full cost for our patients who are being cared for and we have agreed to fund over that cap for the year ending 31 March 2017.” That year runs out on Friday.

And it could be about to get worse.

“We are in discussions with West Sussex [CCGs] because we think they’re going to go the same way,” he says, “which would mean we would have to shut upstairs.” And if that happens, “it will never reopen; that will be it – the end.”

This is amid a quagmire of funding fragmentation, which affects many charities and healthcare services but particularly in the sexual health sector, following the changes made by the Health and Social Care Act 2012, which divided up funding responsibilities.

“If you sat down and tried to make it more complicated you couldn’t,” says Warriner. “HIV is commissioned nationally by NHS England; sexual health, contraception, and HIV prevention is done through local authorities, and abortion through the CCGs.”

The situation facing the Beacon, therefore, is that money could in theory be available if funding structures were simpler.

One option could be to open the inpatient unit up for referrals across the country, rather than only within the county of Sussex, but that requires individual CCGs to agree to contribute, when many are cash-strapped.

Funding for the day service, meanwhile, is equally tangled. Most comes from the local council, but, says Dowe, because that money now comes out of a general public health budget, whereas before it was a specific HIV/AIDS budget, it is no longer ring-fenced.

“There are no guarantees,” says Dowe. “What we’re trying to do is tighten our belt and look at ways of saving money.” Reducing staff is one potential consideration, he says.

On the ground floor, offices are arranged around the living area: a day room with sofas, a TV, and a dining room table. This is where activities, group work, and socialising take place. The workshops have been replaced with DVDs, jigsaws, and board games. Through the doors is the garden, with a pond in the middle and plaques for some of the patients who have died here.

Sitting on one of the sofas near Tim Smith, who made the clock, is a 50-year-old called Stewart Francis. He is a bricklayer, very slim, and speaks with a wheeze in his voice, the remnants of a long-running chest infection.

He was only diagnosed aged 42; it came as a shock, he says, because he had been careful, vigilant, for so long. “It was the only time I let my guard down.” Five years ago, everything started unravelling; a process that led to his referral here.

“One of the reasons I got into depression was the government and the way they were treating me: form after form,” he says, referring to the benefits applications he had to fill in after he became too weak to continue such a physical job.

His sentences start to fragment as he describes the spiral on which he found himself descending. “I just…it just created so much…and that’s when I wasn’t eating properly and my weight dropped and I started drinking. My appetite wasn’t great, so my food intake wasn’t great, so I wasn’t physically capable of doing certain things.”

When some benefits came through, totalling £48 a week, it didn’t spread far enough, he says, so he ended up using food banks. “It used to upset me because I would listen to things on the television and they made you out to be a scrounger and that has a mental effect on you. It makes you feel not only that you’re a second-class citizen but you’re a third class or lower.” He stops and looks down for a moment before inhaling, the wheezing catching his breath.

As Francis’s condition worsened, a community nurse paid him a visit. “He saw me and said, ‘You need to go in.’” Walking through the front door of the Beacon for the first time was overwhelming.

“I got really upset,” he says. “This place was just…it was like a paradise. They showed me to my room, you’re allowed to settle in, I wasn’t interviewed, I was seen that day. They came to your room and knocked on the door as if it’s your home for a week. You became personalised. You actually felt you weren’t in the way.”

The staff and other service users soon started to have an effect on him. “Everyone is relaxed – there’s a pace here and once you start to come down to that pace you start to get better; you feel that you’re somewhere where you’re going to recover.”

He begins to reflect on what is offered here – a level by no means enjoyed by everyone accessing the public or charitable sectors. “I think this sets the standard. As human beings, this is the model, this is the way forward,” he says, pausing for a moment. “I realised after my first visit that this isn’t a high standard; this is exactly the right standard.”

Even the sound makes a difference, he says. “In hospitals, there’s noises and distractions and you’re constantly awake to everything. When I walk around this building, all I hear is the water running in the garden.”

Francis has had three stays here. He says he loves to work, and after each period at the Beacon he has returned to his job before ill health beset him again – most recently with the chest infection, but he is determined to return in a sustained way, so he doesn’t have to rely on either benefits or the Beacon.

But knowing that it is there as a safety net, he says, makes a huge difference to him. He has no partner, and no family nearby. At Christmas, when the chest infection first started, he said to a friend who came to visit, “If it gets back I’ll go into the Beacon and they’ll look after me.”

Without this place, he says, he never would have had the same determination to return to work. On the simplest level, being here makes him happy. “And if you’re smiling, you’re getting better. It’s good for the immune system.”

For Tim Smith, 56, the story of his time at the Beacon arches back to 1996, two years after he was diagnosed.

He was working as a signal engineer on the railways, surrounded by dirt, often working outside on the track, and, he says, picking up infections every five minutes. Eventually, with so many periods off sick, he had to give up work: a huge blow to him – the railway workers, he says, were his family.

After he told the other men he had HIV “they cornered me and I thought, What’s going on here? And they did a speech, they said, ‘You’ve been open with us and we respect that. To come out with what you’ve done, that’s really difficult.’ I was in floods.”

That family, he says, was swapped for the people he found at the Beacon; nurses, doctors, fellow patients. Over the years, he’s had several stays here, and spent hours upon hours in the day centre.

His physical and psychological problems over two decades are a list no one would envy: three bouts of pneumonia; a rash all over his body (a side effect from medication); lung problems, chronic migraines, osteoarthritis in both knees and both elbows, as well as arthritis in his right shoulder and arm; shingles, depression, and suicidal tendencies, brought on in part by the sheer volume of loved ones he lost.

He’s seen friends die here at the Beacon. They were, he says, given “nothing but full respect – respect and privacy. All the staff grieve when they’re gone.”

He talks about his own grief, and about his soulmate who died but doesn’t mention his name. Only when BuzzFeed News asks what he was called is it obvious why he avoided saying it: To do so conjures him too vividly. Smith inhales and forces out “Tom” as if close to touching him. His eyes flood. Twenty years is a blink.

They met in a bar in London in 1990. They became best friends, not partners, unaware how little time they had left. One night in that same bar Smith said to him, “You have something to tell me, don’t you?’” After initially denying it, Tom replied: “OK, I’ve got full-blown AIDS.” Smith reeled.

“I took a deep breath and said, ‘How long?’” Tom answered three years. Everything went black, the floor disappeared, we’re both arm in arm tumbling through a blackness. We were both bawling our eyes out. That’s when I said, ‘I love you, I love you, you can’t do this to me.’ And it’s the abiding time when someone has said back to me, ‘I love you’ and it’s really, really meant…” Smith stops himself, to keep control. It would end up being only 18 months.

He looks around at the day room, the bookshelves, the clock, and the windows through to the garden. The big problem, he says, is survivor’s guilt. He can no longer look at the photo albums of former patients kept here. Meanwhile, he’s lost the best working years of his life and doesn’t fancy his chances getting back into work at 56, with numerous medical and psychological issues.

As well as all the treatment available here, he says, is the human care, the kindness. “You can be yourself. If you want to bawl your eyes out no one is going to ridicule you. If I was feeling suicidal I would tell them.” The mutual support among service users is also key, he says, providing him a purpose. “This place allows me to give.”

He says he felt anger initially when he heard the Beacon’s inpatient unit was under threat, and now sadness, like a bereavement. The centre “must change”, however, as “people are living longer, healthier lives,” he says. “It has to diversify and look at how it can help the community.” The community, meanwhile, are fighting back.

When news emerged of the possible closure, an online petition sprang up, attracting over 10,000 signatures. Members of the public began donating money. The three local MPs pledged their support.

But as BuzzFeed News leaves the Beacon, saying goodbye to staff and service users, two discordant messages ring out. One is from Lisa Power, an HIV policy consultant, who earlier that day told BuzzFeed News that the background to what’s happening in Brighton is stark and in many cases, more troubling, as cuts bite and politics shift.

“The Sussex Beacon is wonderful,” she says. “But realistically a huge number of services have their backs to the wall at the moment. You have massive cuts in almost every service. Literally services closing down in a town. And there are difficulties maintaining access to antiretrovirals in several European countries. What services have to ask themselves is: Are we viable over the next few years?”

The other message still resonating as BuzzFeed News leaves is from Tim Smith. Long-term survivors of HIV, he says, have been forgotten. “It’s like the homeless people that nobody sees. HIV has become the new homelessness. Society doesn’t speak of it, they don’t want to address it, they don’t want anything to do with it because it costs time and money.”