Researchers behind a bold experiment to use hepatitis C-infected lungs for transplant say such organs could help address a critical shortage of donors and make “some good come out” of the increasing number of opioid-related deaths.

Ten patients have received donor lungs from individuals infected with hepatitis C, with eight of the transplant recipients testing negative for the virus following their recovery.

The other two patients have recently started a drug regimen to eliminate the virus.

The transplants were performed at Toronto General Hospital between October and May as part of a study to assess the safety of transplanting hepatitis-positive organs to non-infected patients.

Doctors say the pool of potential organ donors in North America is sadly growing because more individuals are dying from drug overdoses.

“The key part here is that it is allowing us to take advantage, unfortunately, of what we’re seeing too much of -- young people dying -- and at least making some good come out of their deaths because right now we are often unable to use these otherwise healthy organs,” said Dr. Jordan Feld, a specialist from the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease at TGH who is part of the study.

Feld said that about 20 per cent of potential organ donors – and up to 50 per cent in areas hardest hit by the opioid epidemic – carry the hepatitis C virus.

The use of hepatitis C-infected organs to help address a worldwide shortage of organs for transplant is one of the topics being discussed by experts at the Global Hepatitis Summit, starting in Toronto on Thursday. The Toronto team will present its preliminary data at the summit.

“We would estimate an increase of about 30 per cent of our donor pool….these are otherwise very good organs,” said Dr. Marcelo Cypel, a thoracic surgeon at TGH and principal investigator on the study.

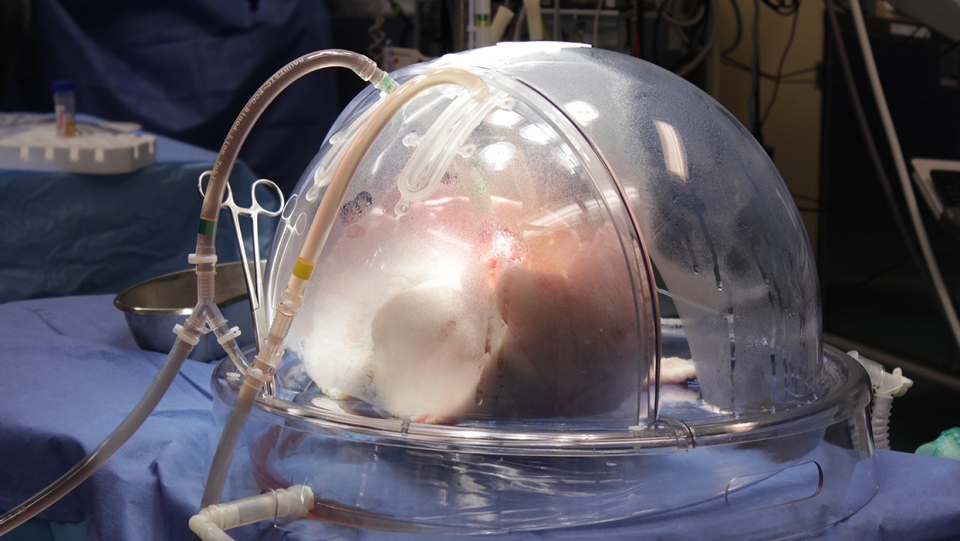

The Toronto team has a two-part approach to transplanting lungs. First, when the lungs are harvested from hepatitis C-infected donors, they are prepared using technology developed at TGH in 2008. The Toronto Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion System (EVLP) is a dome-like device, where the lungs are infused with fluids and nutrients and with antiviral medications to lower the virus count. Doctors say initial results suggest they can remove up to 90 per cent of the hepatitis C virus from the lungs.

After six hours, the lungs are removed from the EVLP device and placed into the transplant recipient. As expected, the virus appeared in the patients’ blood within 2 to 3 days after surgery. The patient is then put on new antiviral medications for 12 weeks to eliminate the virus.

Once a patient is virus-free for three months, the possibility of its return is “one in many thousands,” said Feld.

Accepting hepatitis C-positive donors would increase the number of lungs available for transplant by about 1,000 per year in North America, estimates Cypel. Approximately 2,600 lung transplants are done per year in Canada and the United States.

As of 2016, there were more than 240 patients waiting for a lung transplant in Canada and it’s estimated that 20 per cent of patients die while waiting for lungs to become available.

In the latest lung transplant study, the average age of the donors was 33 and the average age of the recipients was 64. The researchers plan to conduct transplants on a total of 20 patients as part of the clinical trial.

Cypel acknowledges that there is some stigma around hepatitis C and its connection to intravenous drug use but that the technology is in place to eliminate the virus in transplant recipients.

Stanley De Freitas, 73, agreed to receive a hepatitis-positive lung in October, 2017. He had been diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, with his health rapidly declining.

“I realized time is crucial, and I knew it wasn’t getting better, it was going to get worse,” the Toronto grandfather said, adding that his disease was quite aggressive.

When he was offered infected lungs, he was taken aback.

“Hepatitis C? Will I be able to hold my grandchildren? There is a stigma to that, it was troubling,” he said. But he decided that he “had to take” the opportunity.

As soon as the virus was detected post-transplant, doctors started De Freitas on antivirals. Regular blood tests show he is now hepatitis-free and he is breathing well.

“I was quite elated,” said De Freitas.

His daughter Sharon Isherwood said that despite their initial misgivings, the procedure was a lifesaver.

“It’s a real miracle,” she said.

Researchers also plan to study the possibility of using hepatitis C-infected hearts and kidneys, using the same approach.

- With a report from CTV News’ medical affairs specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip