It is now over 50 years since the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was signed, setting the course for the aggressive law enforcement-led charge against drugs we have witnessed over the past five decades. With governments collectively channelling an estimated $100 billion annually into combatting drug production, trafficking and use, one would expect something resembling even the slightest success given such a substantial investment.

And yet, drug markets continue to flourish largely unabated and the number of people globally estimated to have used drugs has risen nearly 20% in recent years, from 206 million to 246 million (2006 to 2013), according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). In light of this, only one logical conclusion can be drawn: the so-called ‘war on drugs’ has been an unequivocal failure, even by its own metrics.

That is not to say that it has achieved nothing at all, though. Indeed, the list of its ‘accomplishments’ is lengthy – albeit being one that proponents of prohibition would rather distance themselves from. Within it is contained a litany of human rights abuses committed in the name of drug control.

The myriad harms of a punitive approach to drugs

For the sake of brevity, what follows is a snapshot of the array of harms caused by punitive drug laws. From fuelling public health crises in the form of HIV and hepatitis C epidemics among vulnerable communities, to manifesting in the execution of hundreds of low-level drug offenders annually – in contravention of international human rights law no less – the deleterious impact of strict drug control is far reaching. Perhaps most present in the public’s mind is the violence associated with aggressive prohibition. For the latest example, one need only to look to the tens of thousands dead since 2006 in Mexico as a result of the country’s militarised drugs strategy.

The axe falls, more often than not, on those at the final point in the drug supply chain: the users.

These shocking examples say nothing of the most direct result of punitive approaches to drugs – that is to say, the millions of people needlessly caught in the criminal justice system. In spite of the professed aims of governments to go after the big players in the trade (the drug traffickers), the axe falls more often than not on those at the final point in the drug supply chain: the users.

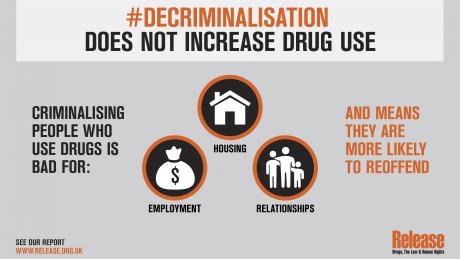

Up to 83% of all drug-related offences in the world are low-level, nonviolent possession offences, placing undue strain on prison systems in many countries around the world, in particular in Latin America, which suffers from endemic rates of pre-trial detention and prison overcrowding. What’s more, even in countries that typically don’t incarcerate people for low-level drug offences, the effect of a criminal record is harm enough in and of itself, significantly reducing future employment, education and housing opportunities, and thus marginalising the individual from society.

Exacerbating this, drug laws are far from enforced evenly, and are often imposed on those already economically marginalised or in ethnic minority communities. For example, in England and Wales, black people are six times more likely to be stopped and searched for drugs than their white counterparts despite having lower rates of drug use, and are far more likely to be charged for possession offences than handed a caution. This disproportionality is reflected elsewhere in the world, particularly in the United States where it has resulted in the mass incarceration of African Americans. Policing approaches such as these have serious implications for police-community relations and can lead to a fundamental breakdown in trust and thus rule of law.

All of this evidence has not gone unnoticed, however, and there is a growing recognition of the enormous failures of criminalisation, combined with calls for a new approach to drug control.

High-level support for drug policy reform

The removal of criminal sanctions for drug possession for personal use (decriminalisation) has gained widespread high-level support in recent years. The Global Commission on Drug Policy – a body comprised of former heads of state, and human rights and global health experts, among others – has repeatedly called for decriminalisation since 2011, and has been joined by several prominent UN agencies, including UNAIDS, the World Health Organisation (WHO), the United Nations Development Programme, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

In addition, the UNODC, the UN body responsible for coordinating international drug control, advocated decriminalisation in a 2015 position paper, albeit supressing its publication immediately prior to release. It has, however, publicly endorsed decriminalisation in joint publications with other UN agencies.

The conclusion to draw from this is that the consensus on what works in drug control has well and truly fractured. This was evidenced furthermore in 2012 when a select few Latin American leaders called for the UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on drugs scheduled for 2019 to be brought forward so as to have an open debate on new approaches to international drug policy, a debate that will now take place this coming April.

Indeed, decriminalisation is not a concept confined to rhetoric – a number of countries have already begun experimenting with it.

The shifting tide towards drug decriminalisation

Recognising the harms that criminalisation causes individuals and their families, and the wasted state resources in governments’ futile attempts to eradicate drug use, many jurisdictions across the globe have responded by implementing a non-criminal justice response to those caught in possession of drugs for their own personal use. This shift from criminalisation to decriminalisation is far from a new one, with some countries having had these policies in place for decades, and research shows that when implemented effectively, the outcomes are hugely positive.

Opponents of ending the criminalisation of people who use drugs argue that to do so would be to open ‘Pandora’s box’, leading to increased levels of drug consumption and, therefore, an increase in health and social harms. However, this position simply does not stack up when we look at the experiences of the more than 25 countries and jurisdictions that have decriminalised the possession of all, or some drugs. In fact, what the experiences of these jurisdictions shows us is that a decriminalised model does not lead to increased drug consumption, but rather can have positive health, social and economic outcomes, as evidenced in some parts of the world.

Perhaps the best-known example of decriminalisation’s successes is in Portugal, which removed criminal sanctions for possession for all drugs in 2001 and now has 15 years’ worth of experience to draw evidence from. The decision of the government at the time to implement a new policy model was in response to a public health crisis amongst people who inject drugs, with high rates of HIV transmission rates and AIDS-related deaths, and a growing visible street drug-using scene.

Portugal’s new policy not only decriminalised possession of all drugs but also invested heavily in public health responses, including a significant scaling-up of needle and syringe programmes, and opioid substitution therapy. The number of injecting drug users subsequently fell by 40% within the first seven years of the new policy, and the cases of people newly diagnosed with HIV fell by 91% from 907 in 2001 to 78 in 2013. And drug-related deaths have plummeted: Portugal now has the second lowest rate in Europe at 2.1 deaths per million of the population compared to the EU average of 16 per million.

For evidence of the broader societal benefits beyond public health, one can look to Australia where two territories and one state decriminalised cannabis in the 1980s and 1990s. None have experienced increases in cannabis consumption since decriminalising, with all areas reporting much lower levels of use than when the policies were implemented, and researchers have shown that the impact of criminalisation has a significant and negative effect on individuals.

In comparing outcomes for people in western Australia who were subject to criminal sanctions for possession of cannabis, to people in south Australia who received a civil penalty, they found that those who were criminalised were more likely to suffer negative employment, relationship and accommodation consequences as a result of their charge for cannabis. Importantly, there was also evidence that those in western Australia were more likely to come into contact with the criminal justice system again, perhaps suggesting that drug laws are a gateway to reoffending.

Besides the arguments for improved health and social outcomes as a result of decriminalising drug possession offences, there is also money to be saved by the state. In the 10 years following California’s 1976 decriminalisation of cannabis, it is estimated that the state saved $1 billion in law enforcement costs. Furthermore, in Portugal between 2001 and 2011 it is estimated that the social costs of drugs fell by 18% as a result of both indirect health costs – largely due to the reduction in drug-related deaths – and costs associated with the legal system. The latter was directly attributable to decriminalisation. It is worth noting that the costs saved to the legal system related to the reduction in criminal prosecutions against people who use drugs, as well as indirect costs saved due to avoidance of lost income and lost production as a result of not sending people to prison or criminalising them for their drug use.

Governments can’t ignore the evidence

It is not a panacea, but it is a vital step in the right direction.

Though over 25 countries have decriminalisation laws in place, this is not to say all implement them effectively, with some imposing administrative penalties that can be equivalent or even worse than criminalisation. Yet, the evidence from countries that have designed effective models is simply too difficult to ignore, to the point where you would imagine it to be enough to persuade politicians to immediately put an end to the needless criminalisation of people who use drugs. But ideology still trumps evidence for a vast number of governments. Disturbingly, here in the UK, the government has admitted that tough sanctions don’t deter drug use, something the UK Home Office concluded in a report in October 2014, but the ‘tough on drugs’ rhetoric continues unabated while drug-related deaths have peaked at an all-time high.

There is still a great deal to learn when it comes to what constitutes an effective decriminalisation model, though thankfully the evidence base to draw from is growing. Millions of people around the world, mostly the young and vulnerable, are locked up, criminalised and are having their future opportunities reduced all in the name of deterring drug use. We must keep shining a spotlight on those countries and jurisdictions that have taken steps to implement policies that are grounded in human rights, health and evidence, to show that there is an alternative and effective approach that will benefit society and mitigate the harms of prohibition.

The decriminalisation of drug possession offences is not a panacea and will not end the ‘war on drugs’. But it is a vital step in the right direction.

Read Release’s 2016 report on drugs and decriminalisation here.

This article is published as part of an editorial partnership between openDemocracy and CELS, an Argentine human rights organisation with a broad agenda that includes advocating for drug policies respectful of human rights. The partnership coincides with the United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on drugs.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.