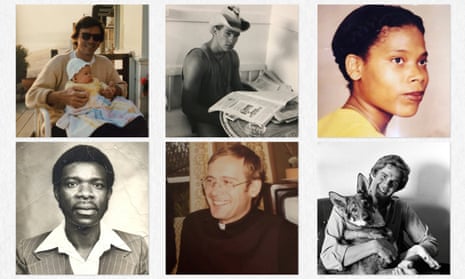

The Aids memorial on Instagram is unlike anything else on social media – there is nothing trifling about it. The first face I look at is of a New Zealand airline host called Barry Hayden – an ordinary man, extraordinary to the people who loved him, the sort of handsome that looks made to last. There is a lightness about the picture, as if there were no end in sight. The man raises a glass of wine to propose a toast. But it is we who must toast him instead. As the Aids memorial’s profile page explains, this is a place for “stories of love, loss and remembrance”. Scrolling through the feed is like looking at an unending family photograph album in which people are related by one thing: Aids, the disease that has led to the deaths of 35 million people worldwide. There are men, women, a handful of children. Not strength in numbers, only mortal weakness. So many gone – seen here in their carefree prime. The faces are mainly young, often beautiful. The collective impact is devastating.

Have we arrived at a turning point – a refocusing on Aids? People seem to be feeling free – or freer – to remember. Artistically, the subject has come back not to haunt but to enlighten us: we have seen Marianne Elliot’s shattering revival of Tony Kushner’s Aids epic, Angels in America; novelists Hanya Yanagihara (New York Times journalist and author of bestselling Aids saga, A Little Life) and Chloe Benjamin (The Immortalists) have, in diverse ways, taken Aids as a way of meditating on mortality and Russell T Davies, author of Channel 4’s Aids drama The Boys, which will go into production next year, has recently said he was motivated partly by the wish to ensure that the era of epidemic, with all its losses and friendships, be not forgotten. And just this week, the poet Kayo Chingonyi gave a breathtaking talk, Blood, on Radio 3, about his parents who died of Aids in Zambia and said it was only now that he felt ready to broach the subject and “knock shame on the head”.

And now this Instagram site – the most unlikely vehicle for recording history – has taken off – especially in the US (4.451 posts; 59.8k followers). The Aids memorial was started in April 2016 by Stuart, a Scot who prefers to keep himself – and his surname – out of the story. Each contributor emails or messages Stuart with the story of a friend or family member affected by HIV. He then posts their text and pictures on to the Instagram feed. If you don’t have a photo of your loved one, he’ll help you find one. If no image exists, an illustration by artist Justin Teodoro will be used instead. This was never a vanity project and Stuart is no fan of social media’s narcissistic routines. Nor does he swank about educating a younger gay generation, even though his site succeeds in doing exactly that. “It’s still taboo to talk about Aids, I thought maybe I could help change that,” he says. “History does not record itself, Instagram reaches a far-ranging demographic.”

The feed has taken off, especially in the US, and has more than 4,500 posts and 67,000 followers. It has attracted high-profile supporters such as Tatum O’Neal, Shirley Manson and Alan Cumming, who appear wearing their Aids memorial T-shirts and posting messages of solidarity. Peter Spears, producer of the film Call Me By Your Name [a gay coming-of-age story], saluted the Aids memorial in his speech at the GLAAD awards in May. One of the posts, he said, about “the mystery of first love” explained the way they made their film. The Aids memorial is, in contrast to the famous Aids quilt – at 54 tons the largest community artwork in the world – a weightless gallery, dominated by photographs. Celebs and non-celebs are remembered and some entries (written either by Stuart or by people who knew them) are about people you may not be aware had the disease, such as 70s tennis superstar Arthur Ashe or actors Anthony Perkins and Alexis Arquette.

Stuart laments the stigma around Aids, even within the gay community: “On dating apps, there are those who seek to date only men who are ‘clean’. There are people fearful of being tested, afraid of what their family – or society – might think were they to test positive. They end up dying because they left it too late. HIV diagnosed can be treated, it’s no longer a life sentence.” Occasionally, Stuart adds, people intending to post have changed their minds at the last minute, fearful of judgment.

In a superb compendium of a piece about Aids in the London Review of Books, Tom Crewe describes how the search for treatment was impeded “by politics, by journalists, by squabbling and prejudice and injustice”. He describes victims victimised by hospitals, losing jobs and health insurance and being evicted from their homes. And there is no shortage of evidence of this punitive prejudice on the Aids memorial site. I was particularly struck by the moving photograph of a contemplative Ray Petri, the Buffalo stylist and designer who died in 1989, with a commentary by his friend, stylist Mitzi Lorenz, on how the Royal Free Hospital in Hampstead failed in their duty of care. She remembers feeling unable to talk about what was happening and being scared: “We had so little information about the disease other than those awful TV adverts of a tombstone falling to the ground.”

Nora Burns, a New York-based actor, has posted a tender, handwritten note in pencilled capital letters from her best friend, David, whom she met aged 17. He got Aids at 24 and died, in 1993, when they were 31. She describes him as a “hustler” and an “artist” and has made a one-man show, David’s Friend, about him, a hit in New York which, she hopes, is coming to London. Her voice is not always steady as she recalls: “We had a shorthand for how we talked, the same dark humour. He was sexual and handsome and unique – so ahead of his time.” She remembers how every day’s newspaper, in the early 90s, brought news of another friend’s death in its obituaries column. She believes we are now having a massive delayed reaction to the epidemic. In her show she declares: “The PTSD is wearing off… there’s a realisation of our losses, losses we were too young and overwhelmed to take in, goodbyes we didn’t get to say, ‘I love yous’ that came too late.” She tells me: “It’s a bit like the Holocaust. Twenty years later and you go: what the fuck happened?”

The Aids memorial is full of harrowing surprises, such as the post by Ashlee Foster about her addict mother in which she addresses her as though she were still alive: “I was nervous that you would get high and forget about me.” It is necessary to tell her mother’s story but she admits, “what’s hard is the judgment I receive once I tell people my parents died from Aids. They either assume I have it or shun me because they don’t know my status.” Yet she has also had “awesome” feedback. “Aids took everything from me and made me an orphan. I will never downplay this horrible epidemic.”

You might assume the contemplation of all these deaths would turn mawkish but, as Stuart rightly claims, the feed is not depressing: “Ironically, it’s the opposite.” The feed’s brave hashtag, “what is remembered lives”, is endlessly appropriate. Yet, when I ask about posting these stories day-in, day-out, he admits: “It’s difficult. Sometimes, I feel too emotionally drained to continue. However, I sleep on it. I don’t stop. There’s more to each post than death. I’m reminded to live life to the full, appreciate the people closest to me, be more compassionate, less judgmental, not to sweat the small stuff. I relapse constantly but these daily reminders call me to action.”

The Aids memorial and its gallery of fleeting faces is a reminder of a different kind too. In particular, it recalls Derek Jarman who wondered whether (in his Aids journal, Smiling in Slow Motion) he should be seeking “deep” thoughts in the face of death but concluded: “The surface is more interesting and alive like the skin”. It is a site that sees depth in the surface image, in the snapshot of the beloved. Oscar Wilde would also have approved for, as he observed with taunting truthfulness: “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.”